De siste årene har det vært et økt fokus på hvordan musikkspillere kan skade hørselen. WHO gikk i vår ut og sa at over 1 milliard ungdommer står i fare for å få hørselsskader som følge av for høy musikk på ørene. I den forbindelse har det stadig vekk vært slått opp i media, både nasjonalt og internasjonalt, at man bør unngå å bruke øreplugger, såkalte «earbuds» eller «in-ears».

Kommunikasjonsakustikk

A brief history of electroacoustics, pt. 6:

Various loudspeaker mechanisms

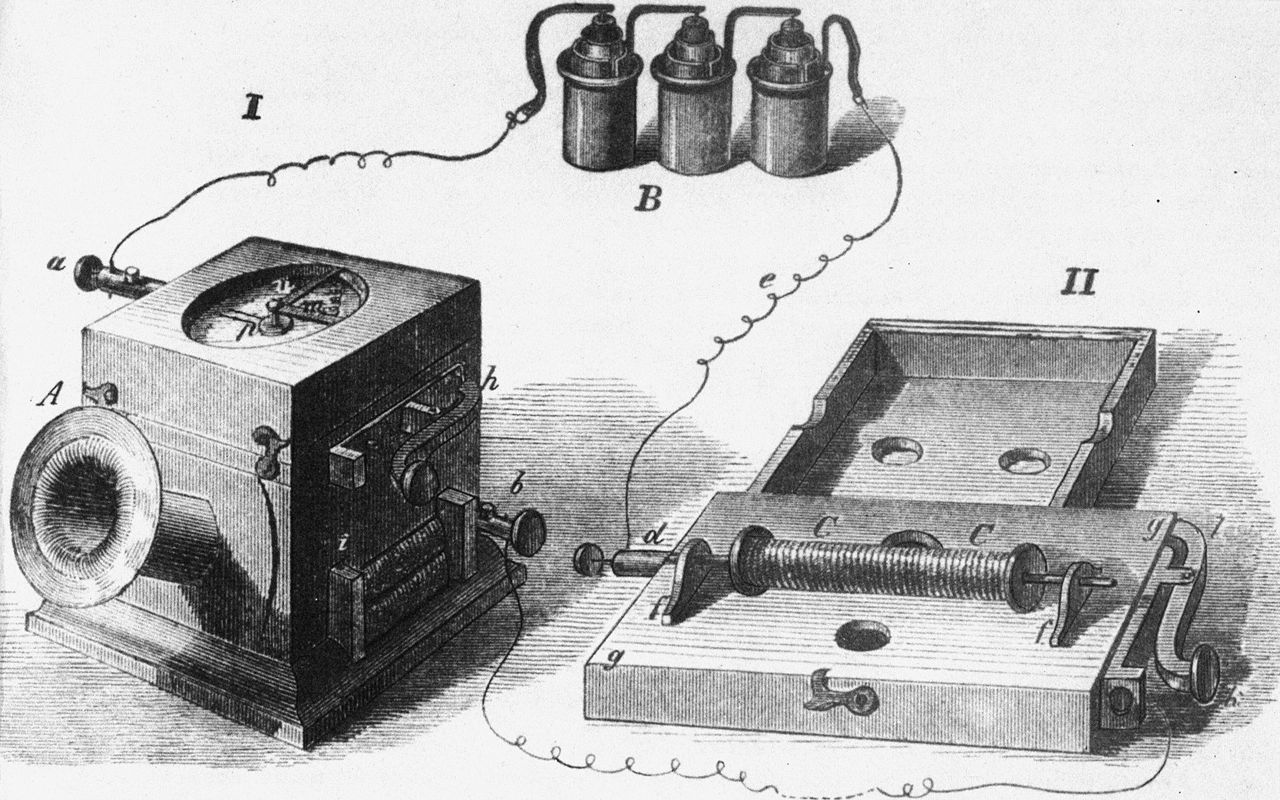

The invention of the telephone set off a wave of creativity, and almost all conceivable transducer mechanisms were tried out in the 1870s and 80s. Some of them developed into usable devices, others serve mainly as illustrations of man’s creativity. In this part, some of them will be presented, ranging from useful, mainstream designs to the downright bizarre.

Read more…A brief history of electroacoustics, pt. 6:

Various loudspeaker mechanisms

A brief history of electroacoustics, pt. 5:

Moving coil loudspeakers of lasting impact

In Part 4, we looked at various early variants of moving coil (or moving conductor) loudspeakers, including predecessors of the modern moving coil cone driver. In this part I will present two specific designs that made a lasting impact on loudspeaker technology. One is a direct radiator; the other is a horn driver.

In the early part of the 1920s, many researchers were working on loudspeakers, based on various principles. E.C. Wente at the Western Electric Engineering Department (to become the Bell Telephone Laboratories) worked on a small direct radiating moving coil loudspeaker that was later patented (US patent 1812389, filed April 1, 1925 and granted the same date 1935). In England, Paul Gustavus Adolphus Helmuth Voigt at Edison Bell also worked on moving coil loudspeakers and microphones. In May 1924, he applied for a patent on a moving coil loudspeaker, but unfortunately a little to late. He was beaten at the finish line by two engineers at the General Electric Company, C.W. Rice and E.W. Kellogg.

Read more…A brief history of electroacoustics, pt. 5:

Moving coil loudspeakers of lasting impact

A brief history of electroacoustics, pt. 4:

Early moving coil loudspeakers

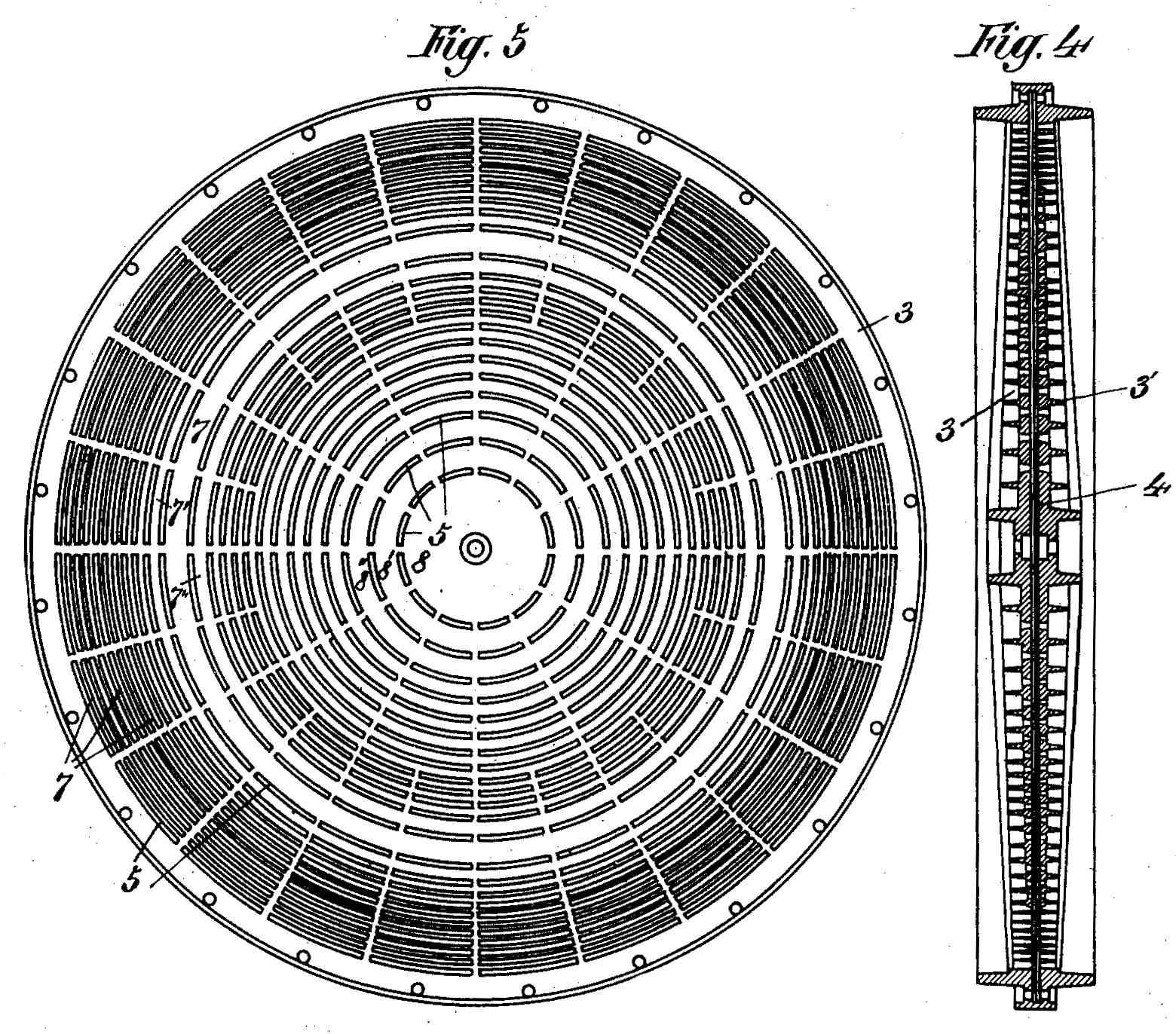

The moving coil loudspeaker is without doubt the most common electroacoustic transducer in use. It consists of a circular coil suspended to move freely in a radial magnetic field. This transducer principle was first described by Ernst W. Siemens in his 1874 patent. He describes his transducer as a means for “obtaining the mechanical movement of an electrical coil from electrical currents transmitted through it.” He also mentions that the coil could be used to move visible or audible signals, but he had obviously nothing more elaborate in mind than a bell or buzzer.

Read more…A brief history of electroacoustics, pt. 4:

Early moving coil loudspeakers

A brief history of electroacoustics, pt. 3:

Microphones

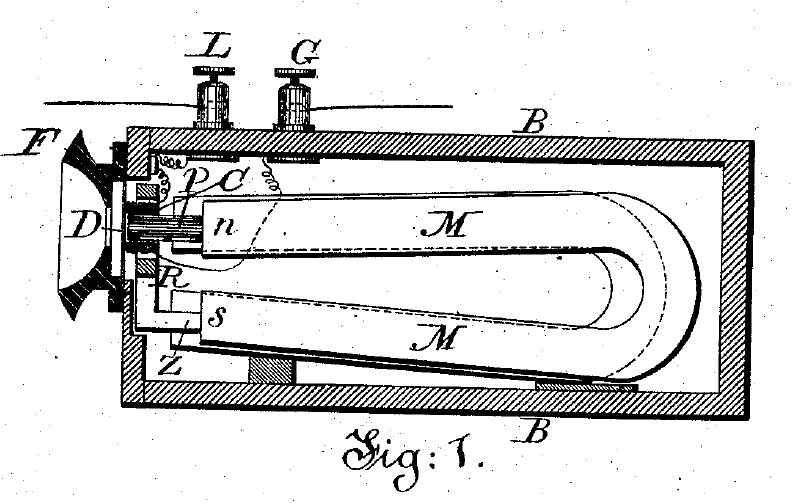

In the preceding parts, I have mentioned several microphone (transmitters, in telephone lingo) types that were used in early telephone experiments. The first type, the one described by Borseul, was a make-and-break type transmitter, which was used by Reis. This type of transmitter is not very useful, and can hardly transmit understandable speech. The very closely related loose-contact transmitter, is the basis for the carbon microphone. Also related is the variable resistance transmitter used by Elisha Gray in his bid for the telephone. A needle was attached to the transmitter diaphragm, and the other end of the needle touched the surface of a conductive liquid in a conductive cup. When the diaphragm vibrated, the needle made more or less area in contact with the liquid, and the resistance of the circuit varied.

Read more…A brief history of electroacoustics, pt. 3:

Microphones

A brief history of electroacoustics, pt. 2:

The telephone

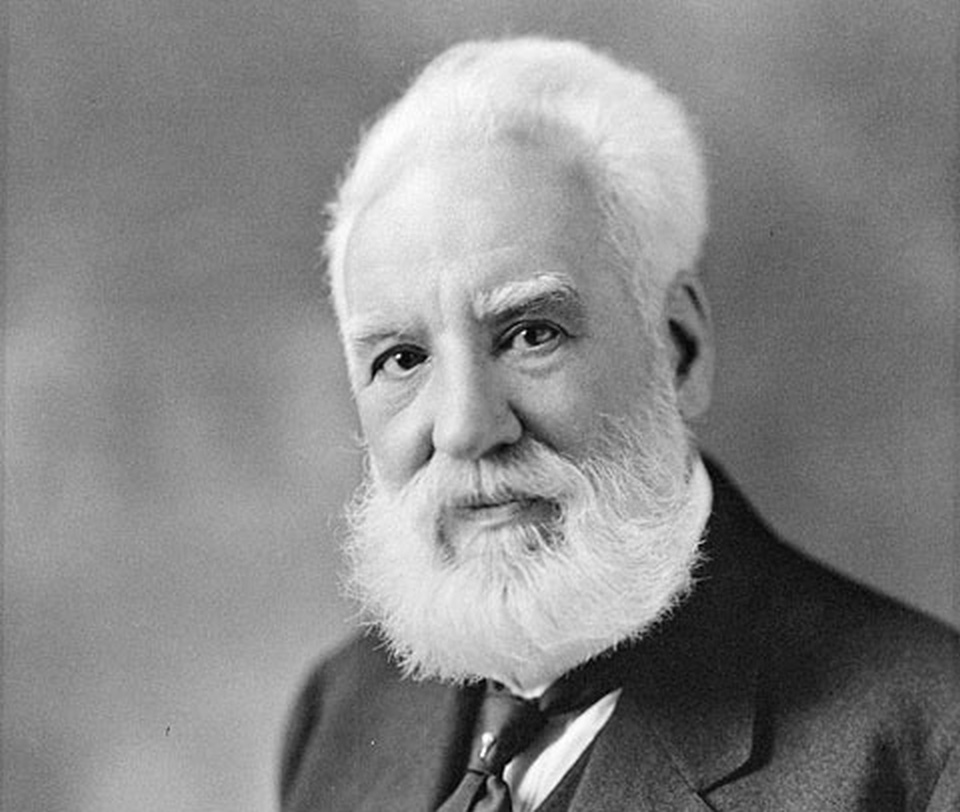

Two inventors with significantly improved, successful telephone devices made it to the patent office on the same day, February 14, 1876. These two inventors were Elisha Gray (1835-1901) and Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922).

Read more…A brief history of electroacoustics, pt. 2:

The telephone

A brief history of electroacoustics, pt. 1:

The birth of electroacoustics and early telephones

While electroacoustics is as old as lightning and thunder, man’s controlled application of it dates back to the 18th century. Early electroacoustic phenomena were mere replicas of the natural occurring ones; the crackles of electrostatic discharges in the early experiments in electricity. In 1729, it was discovered that some materials conducted electricity, and the idea that this could be used to transmit intelligence was born.

Hvordan snakke i telefonen?

Du trenger kanskje ikke å rope? ARCs professor Peter Svensson ved NTNU har nylig blitt intervjuet av Dinside om hvorfor folk roper i telefonen likevel. Kjernen er Lombard-effekten, altså at du naturlig justerer stemmenivået og stemmeleiet ditt etter støyen rundt deg og stemmenivået til samtalepartneren din. Det kan derfor altså være lurt å redusere både ditt eget stemmenivå og avspillingsnivået i telefonen din.

Du kan lese hele intervjuet hos Dinside. (Øh…du kan også gjerne se bort fra overskriften.)

Bildet er hentet fra Wikimedia Commons

Hvor normal er normal hørsel?

Mange har nok sett Leif Justers harselering med meteorologenes bruk av uttrykket «mot normalt» under værmeldingen før i tiden (hvis du ikke har det kan du se klippet nedenfor). Han gjorde et humoristisk poeng ut av bruken av «det normale».

Normalisering gjøres i mange sammenhenger. Hvis du f.eks. ønsker å si noe om en ny måling du har gjort, kan du sammenligne med det «normale» for å lettere kunne vurdere om verdien du har fått er stor eller liten.

Man finner ofte det normale ved at man tar gjennomsnittet av målinger fra en (stor) gruppe. Hvis du f.eks. tar gjennomsnittet av høyden til alle elevene i klassen (som sikkert alle har gjort en gang i oppveksten) finner man ut hvor høy den «normale» eleven er. Ironisk nok trenger ikke en eneste person å ha denne «normale» verdien, men det er likevel dette som er normalt.

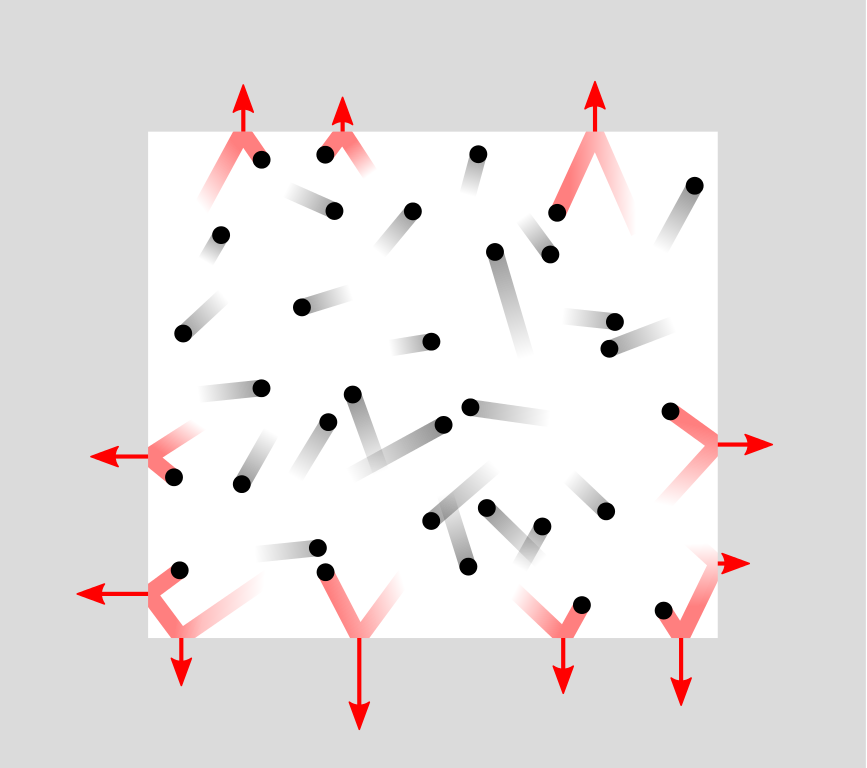

Hva er egentlig trykk?

Lyd er noe vi alle har hørt om. Det vi oppfatter som lyd er variasjoner i lufttrykket på trommehinna. Disse variasjonene forplanter seg dypere inn i øret og deretter inn i hjernen. Trykk er derfor sentralt for akustikere og alle andre som jobber med lyd. Her vil jeg minne deg på hvor lufttrykk egentlig kommer fra, og si litt om hvordan lufttrykkets natur begrenser hvor bra øret og mikrofoner egentlig kan bli.