In Part 4, we looked at various early variants of moving coil (or moving conductor) loudspeakers, including predecessors of the modern moving coil cone driver. In this part I will present two specific designs that made a lasting impact on loudspeaker technology. One is a direct radiator; the other is a horn driver.

In the early part of the 1920s, many researchers were working on loudspeakers, based on various principles. E.C. Wente at the Western Electric Engineering Department (to become the Bell Telephone Laboratories) worked on a small direct radiating moving coil loudspeaker that was later patented (US patent 1812389, filed April 1, 1925 and granted the same date 1935). In England, Paul Gustavus Adolphus Helmuth Voigt at Edison Bell also worked on moving coil loudspeakers and microphones. In May 1924, he applied for a patent on a moving coil loudspeaker, but unfortunately a little to late. He was beaten at the finish line by two engineers at the General Electric Company, C.W. Rice and E.W. Kellogg.

The Rice-Kellogg loudspeaker

Early in the 1920’s, Rice had suggested to Kellogg that they should look into making the best possible “hornless loudspeaker”. The director of the General Electric research laboratory, Dr. W.R. Whitney, endorsed the project, and agreed that the research should be done without imposing restrictions based on commercial practicability. The result of this project was a loudspeaker that was so good that in a few years, it had driven nearly all other types from the market.

Prior to the publication of their monumental paper, it had been widely believed that to get enough loudness, one would have to rely on resonance. One reason for this belief was that there was not really that much power available. So one of the first things Rice and Kellogg did was to produce a laboratory amplifier capable of delivering enough power to permit them to not rely on the efficiency at resonance to achieve the necessary loudness. From this point on, they could concentrate on the quality aspect of the loudspeaker instead of the quantity. They soon realized that the loudspeaker would produce a flat frequency response if operated above its fundamental resonance. In the low frequency range, the radiation resistance is very low, and the diaphragm mass is the dominating factor. The loudspeaker operates in a constant acceleration mode, and since the radiation resistance at the same time increases, it will produce a flat frequency response.

Due to the very limited output of contemporary radio receivers, the Rice-Kellogg loudspeaker was sold with its own built-in power supply and power amplifier, as the Radiola Model 104, making it the world’s first stand-alone active loudspeaker. The power supply had some reserves, so an outlet was provided to power the Radiola model 28 radio, making a complete batteryless receiver. The combination was enthusiastically received, even with the 1926 price for the 104 alone of $250.

The moving coil cone loudspeaker, designed after the manner of Rice and Kellogg’s design, is still the most popular loudspeaker driving mechanism on the market. The reason for this is perhaps that while extremely good cone drivers are expensive and hard to make, it is also hard to make an extremely bad one.

The Wente-Thuras receiver

In 1925-26, the engineers at the Bell Labs were working franticly to finish the equipment for what would become a booming industry during the 1930s: sound film. Western Electric and Bell Labs had teamed up with Warner Bros., the only film producers interested in sound film technology at the time (all others had been scared away by several expensive failures over the past decades), to launch the Vitaphone sound film system in 1926.

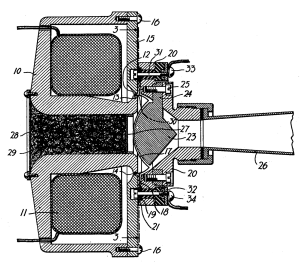

Western Electric were already producing public address systems, but these used moving armature drivers, which had limited linearity and frequency range. Something better was needed for film sound, in order to create the perfect illusion. The solution came in the form of the Western Electric 555-W horn driver. Designed by E. C. Wente and A. L. Thuras in 1926, patented two days before the Vitaphone premiere, it is the grandfather of the modern horn compression drivers. It has many of the features of modern horn drivers: edge wound aluminium voice coil, a domed aluminium diaphragm, tangential corrugated suspension, and a phasing plug.

As the horn provides a fairly constant, resistive load, mass control of the diaphragm movement is not desired. Instead, the diaphragm can be made small and light, a factor which, together with the high magnetic flux, resulted in a loudspeaker with an efficiency of 30% on mass production basis over a 60 Hz to 3 kHz frequency range, with an unprecedented power capacity.

This loudspeaker, on the proper horn, is still considered to be very good, and is a collector’s item fetching premium prices. And, speaking from personal experience, it provides a good reality check when evaluating the latest and greatest audio equipment.

Images from Wikimedia Commons and published patents