The 1920s saw much development in horn loudspeakers, and loudspeaker in general. Western Electric already had their microphones, amplifiers, straight exponential horns, and very good balanced armature transducers. At this time, much research was also put into disc recording and reproduction at the Western Electric Engineering Department, and simultaneously, optical recording of sound was also in progress, using Wente’s Light Valve. The time seemed ripe to attempt sound film. The story has been told elsewhere, but in short, most of the industry turned down Western Electric’s offer. They “knew” sound film would not work. But the Warner Bros found in the WE system something that could help them beat the big guys in the industry, and after the success of their first sound film, the rest is history.

It is likely that nothing had more influence on professional high-quality sound reproduction than the work done to improve sound reproduction in theatres, from the mid-1920’s and forward. And it is likely that no-one made greater contributions to the art than the scientists at at BTL and RCA.

The next theoretical step for horns was Hoersch’ investigation of the existence of “non-radial vibrations” in conical horns, i.e. higher order modes, in 1925. This is perhaps the first treatment of this phenomenon in horns. Little was however done on the subject for years.

In his 1928 thesis, and in a 1932 JASA paper, William Hall presented measurements of the phase and amplitude of the sound field inside conical and exponential horns. This clearly showed the shortcomings of the simple horn theory of Webster, and Hall hoped, in vain, that better horn theory would evolve to take these effects into account. At the same time, Sato published a theoretical and practical study of the directional properties of conical horns, a study that seems to be largely overlooked.

Another horn type, the catenoidal horn, was patented by Edward Norton of BTL in 1929, but it seems to have gone largely unnoticed until Salmon presented the family of hyperbolic-exponential horns in 1946, where the catenoidal horn is one limiting member of the family.

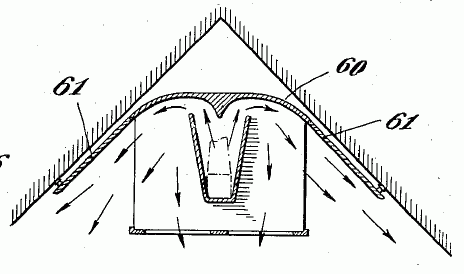

At this time, the idea of reducing the size of the horn by utilizing a corner seems to have surfaced for the first time. Maximilian Weil seems to be the first to take advantage of corner placement in his gramophone patent. More explicit is E.K. Sandeman’s design from 1929, which uses all three surfaces of the corner. This method was taken up by Kellogg in 1931.

Voigt, around 1933, made another type of corner horn by splitting his cinema tractrix horn into four, and placing one fourth in the corner, pointing upwards, with a reflector on top to direct the high frequency sound out into the room.

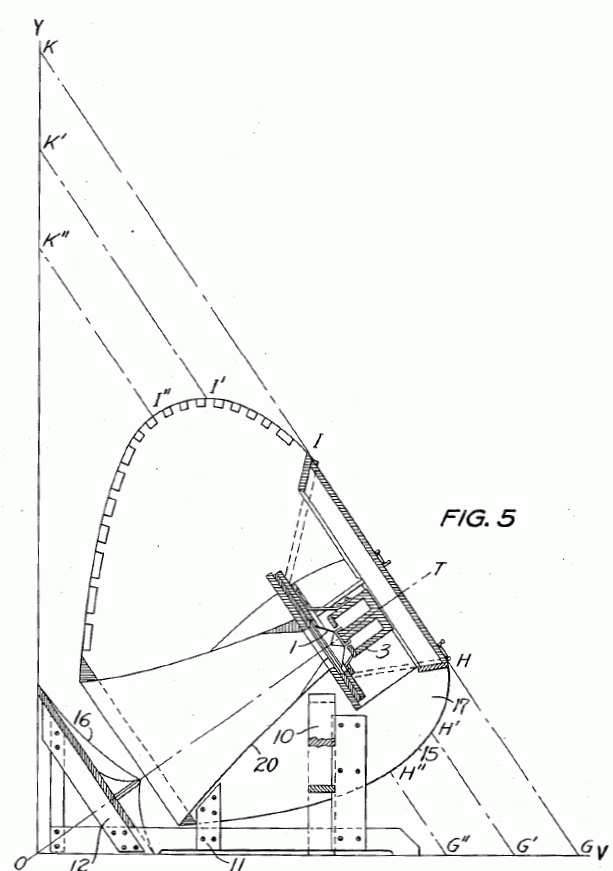

In 1940, Paul W. Klipsch patented another corner horn (US patent 2310243) which became a successful commercial product that is still in production.

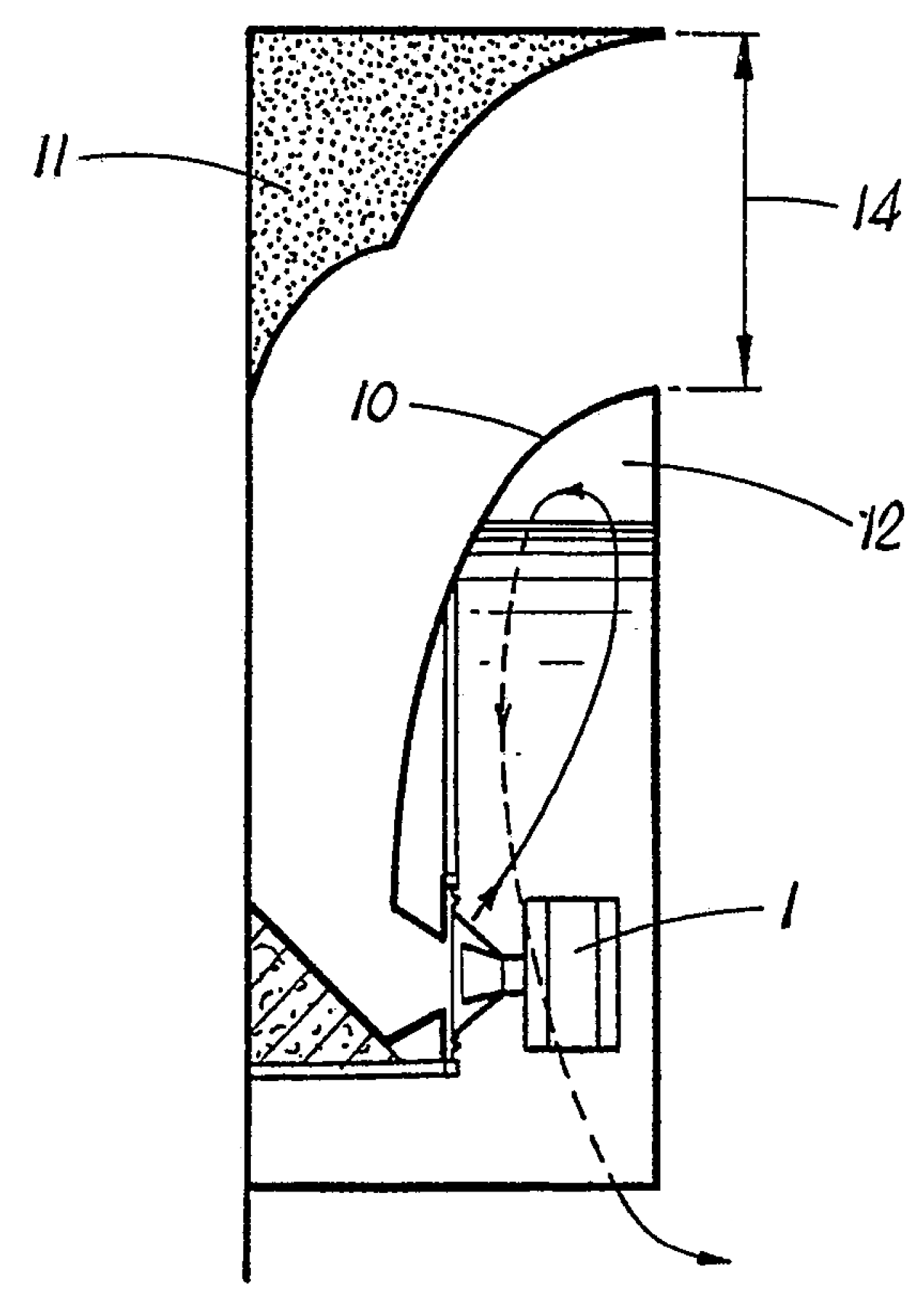

The 1930s saw much practical development of horns. In 1933, BTL experimented with a large three-channel high-quality system using the first single-driver multicellular horn, and a large folded bass horn, both designed by E. C. Wente. The system, called the Fletcher System, was probably the best sound transmission system built to that date. Due to its high quality, the Fletcher System aroused the interest of the MGM, who wanted to put it into production for installation in their theatres. John K. Hilliard contacted BTL in 1933, but did not receive any reply for a year, when he was told that they were not interested in producing this system. Hilliard proposed to Douglas Shearer, head of MGM’s Sound Department, that they went ahead and did the work themselves, to which Shearer agreed. Hilliard’s team included Robert L. Stephens (of Stephens Trusonic, a major Hi-Fi manufacturer in the 1950s), who designed the multicellular horns for the new system, James B. Lansing (of Altec Lansing and JBL), who designed the drivers, John F. Blackburn, who designed the phasing plug for the high-frequency driver, and Harry F. Olson, who designed the folded bass horn. The resulting system was very successful, and it received a technical achievement award at the 1936 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences ceremony. This system, and versions of it, was the industry standard for many years.

All images from published patents